What does it take to build strong bones?

In the last journal club, we reviewed a study that showed no change in the bones for a group of females that trained with resistance and cardio exercise for 24 weeks. I mentioned that we will be looking at this topic over time. So here we are.

As most everyone who has grown up in the U.S. knows, we want strong bones and we don’t want osteoporosis as we age. We’re told to get our calcium and to be active in order to build strong bones. To that end, the authors of today’s paper cited studies that found active folk as a group have stronger bones than sedentary folk. Let’s ask, what kind of activity builds strong bones? One possibility that comes to mind is the activity we here love so much: resistance exercise.

Today’s researchers provide 3 reasons to empirically test whether resistance exercise can help females, specifically, build strong bones.

- Lifting weights hits on the accepted mechanisms that trigger bone growth.

- Female strength athletes have stronger bones than “normal” folk or endurance athletes.

- Strength and muscle mass correlates well with stronger bones in the general population.

Despite the above correlations, the authors are upfront about the very mixed success rate that resistance exercise experiments have with strengthening bones. Because bone growth in adults is slow, prior studies may have been too short to show an effect. Also, the stress on the bones may need to be more intense to produce an effect. Today’s study sought to address these prior limitations. The title is, Twenty weeks of weight training increases lean tissue mass but not bone mineral mass or density in healthy, active young women.

Methods

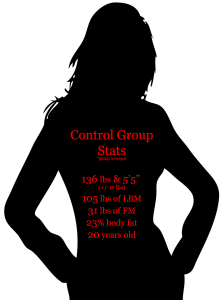

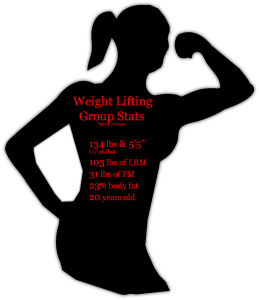

This study lasted 7 months and had all female participants. They were newbies to resistance exercise, while still active folk. Twenty of them were in the lifting group and ten of them were in the comparison group. Below are the descriptive stats for the lifting group. The comparison group’s stats were the same. As always, they’re group averages and rounded to the nearest whole number for the ease of viewing.

This study was an examination of the effect of resistance exercise on bones. Thus, the participants were not put on a diet or told to change their normal eating pattern. Their reported food consumption was assessed throughout the study. Their calcium intake met the recommended daily amount. The average daily kcals reported by the lifting group was 1757 (+/-513) and the control group reported 1638 (+/-426).

DEXA scans were taken to measure pre/post FM, bone, and non-bone LBM.

The lifting participants were split into 2 groups. One group trained their whole body in one 1-1.5 hour session. The other group trained their upper body 2 days a week and their lower body another 2 days a week. The different ways of training did not result in any differences and was published separately. All lifters did 4 exercises, each for 5 sets of 6-10RM, for their upper body during each of the respective sessions. All lifters did 3 exercises, each for 5 sets of 10-12RM, for their lower body during each of those respective sessions. All lifting was done using machines and with trainers. Lifters were constantly pushed to increase the weights they used throughout the study. Pre/post strength tests were done for the bench press, leg press, and arm curl.

Results

As the study title says, resistance exercise did not result in overall changes to the BMD. The only change that occurred was the control group lost 2% in their thoracic spine.

As we can expect, the lifting group got stronger, gained LBM, and lost FM. The comparison group did not change.

The lifters increased their average muscle strength by 33% in the bench press, 23% in the leg press, and 73% in the arm curl.

The lifters lost 1.1% of their average body fat.

The lifters increased their LBM by 3.7% for an overall gain of 3.3 lbs. That mass was distributed as 0.88 lbs on their arms, 1.54 lbs on their torso, and 1.1 lbs in their legs.

Thoughts & Implications

Building strong bones is no simple or easy task. These participants were pushed for 7 months and they did not produce any change in their bones. Perhaps one clue is from their program design. They specifically trained to build some muscle, and they did (Side bar: they trained with personal trainers for 7 months, getting stronger, and slapped on 3.3 lbs…not exactly “getting bulky”). Maybe the mechanisms that drive muscle development only overlap with those that drive bone growth/density. Training for muscles may not necessarily mean strong bones.

The Nitty Gritty

The authors made some key points in their discussion of the results that I think need repeating here. First, these participants trained in RM ranges that did not get “heavy”. The mechanical stress needed to elicit bone growth may need to be heavier. A training program that regularly involves heavy lifting may be what is needed. On the other hand, the rate of building strong bones is not fast. We may need to train for many years in order to get that benefit.

If a study did find a statistically significant increase of 1-2% within a year, then what is the clinical significance of that? Does a 1-2% difference mean less broken bones? The studies that find athletes have stronger bones than the general population report a difference on the level of 10% and higher, depending on the specific site. That’s with athletes who have weight trained for 2+ years. Compound that with the understanding from research that up to 80% of our bone strength may be accounted for by individual genetics. Perhaps these healthy and young female participants already had strong bones before starting the study. Perhaps the healthy, active, and young are not the ones whose bones would benefit from resistance exercise. Maybe resistance exercise can prevent the weakening of our bones.

Plain & Simply

When we pause long enough to ask exactly what kind of activity will help us develop strong bones, we realize how complicated the answer is. The simple prescription to be active or to lift weights is not exactly accurate. The young and healthy may need to work hard for a while in order to build strongER bones. The inactive or older may not need to train so hard for so long. Thankfully, resistance training has been shown to help young and old in more ways than strong bones: protecting/fighting against such ills as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, immobility, (apparently) cognitive decline, etc. We’ll search for more answers in future journal clubs!

If you have any questions about this study or anything I said, please feel free to leave a comment. I will get back to you and others may have insight to offer, too. If you have any questions or topic suggestions that you would like answered as a post, then please email me at robert@analyticfitness.com.

Don’t forget to like Analytic Fitness on Facebook, or follow me on Twitter or the other social medias!

POST REPLY