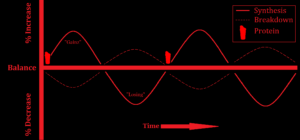

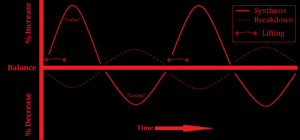

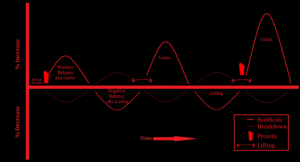

An interesting avenue of research is the examination of protein synthesis and breakdown together (Deutz & Wolfe, 2012, Kim, et al., 2015, Lemon, et al., 1992, Moore, et al., 2012, Pennings, et al., 2012, Tarnopolsky et al., 1988).

Most exercise studies look at protein synthesis alone, which in this case is the response of muscle cells to training stimuli or to protein ingestion. Synthesis repairs and builds new muscle tissues, structures, and cellular machinery (Atherton & Smith, 2012). Protein breakdown is the replacement of old and damaged proteins from cells/tissues in order to make repairs and to facilitate new growth and adaptations.

Examining these processes together allows us to get a more dynamic and accurate view of the muscle repair and growth process. A sum positive balance between these two states can be described as overall muscle growth, or “Anabolic”. A sum negative balance between these two states can be described as muscle loss, or “Catabolic”. Breakdown can be greater than synthesis in completely fasted conditions or in disease states.

In fed conditions, synthesis is usually greater than breakdown.

Exercise also temporarily increases synthesis, and can increase breakdown if no food is eventually consumed.

Food and exercise together, over time, drives a positive balance between synthesis and breakdown which leads to muscle growth and training improvements.

What do some of these “balance” studies tell us?

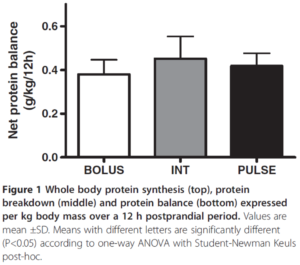

The Tarnopolsky (1988) and Lemon (1992) studies examined whole body nitrogen balance, which has limitations as far as how much it can be an accurate proxy for direct muscle building. Both studies showed higher nitrogen balance levels from very high protein intake. Yet, neither showed any improvements in strength or body composition. The Moore (2012) study also examined whole-body nitrogen balance for 3 feeding patterns across the day. Whether consumed as many little hits of protein or 2 large hits, the balance of protein synthesis and breakdown overall was not different between the groups.

Moore, et al. 2012

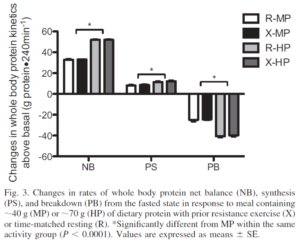

This study was an acute one, though, and differences could develop over time. The van Loon (2012) study was also an acute study. They found that higher amounts of protein increased net balance. These results may not hold up under chronic consumption of high amounts of protein. The study was also done in older males. They are known to likely require higher amounts of protein than young males.

van Loon, et al. 2012

The Wolfe (2015) study was also an acute study, but showed the same net balance result.

Wolfe, et al. 2015

For sure, these studies show that protein balance can be increased from high amounts of protein consumption. We cannot forget, though, that these levels of synthesis and breakdown are minute in absolute magnitude and the sum of their difference may require a long time before we can notice anything.

The Antonio (2014 & 2015) studies can offer some possible insight into this. In the face of very high daily protein levels, the 2014 study did not find any difference in body composition. The 2015 study found that both high and very high protein groups gained 3 lbs of lean body mass, and only the very high protein group lost 4 lbs of fat. These Antonio studies were effectively a test of consuming very high levels of protein over months and they did not seem to show an added benefit to lean body mass.