What happened to the slowing metabolisms of the “Biggest Loser” contestants after six years?

Last week, a research team that we’ve featured here before published a follow up to their “Biggest Loser” study. This publication came with a big piece in the NYTimes, an NPR discussion, and a Science Friday discussion among so many other news stories. It’s blown up on the web.

There is much to say about this study, how the media has covered it, and what the results mean to the world at large. As we like to be analytical here, we’re going to start today by just looking at what exactly the follow up study even did and what the results are. Rather than discuss this topic based on the media, let’s go directly to the source!

Methods

If you have not already, take a moment to read our previous journal club on the original 2012 paper. We discussed the methods in detail.

For this follow up, 14 of the original 16 season 8 (2009) “Biggest Loser” contestants returned. The contestants had a number of measurements taken. Aside from weight, they had more blood tests, DEXA scans, resting metabolism (RMR), and their total daily metabolisms measured using Doubly Labeled Water (DLW).

Results

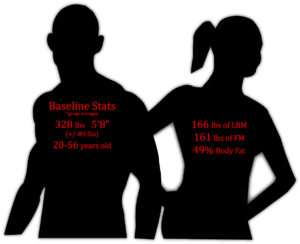

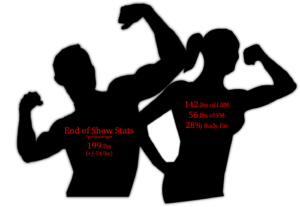

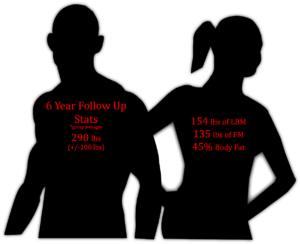

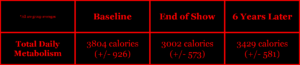

Below are the descriptive stats for the participants at the start of the show, the end of the show, and 6 years later.

@ start of the show

@ end of the show

6 years later

On average, the contestants maintained ~12% of the weight they lost from their original starting weight. Unlike most studies of weight loss maintenance over time, 57% of the contestants kept off at least 10% of their original body weight. Follow up studies of just a year out have much worse outcomes than this group.

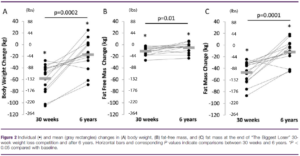

Below is a figure from the paper that shows the individual weight changes over time, including the changes in fat and lean mass (LBM).

Below are their total daily metabolisms when the show started, ended, and 6 years later.

Their total metabolisms decreased by the end of the show, which we would expect given that they lost so much weight. Six years later, their total metabolism went back up with their increase in weight, though not to the same level as they started at.

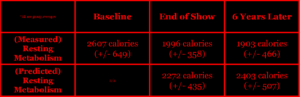

Below are their resting metabolisms at the start of the show, the end of the show, and 6 years later. As well, you will see what their predicted resting metabolisms were based on their starting stats.

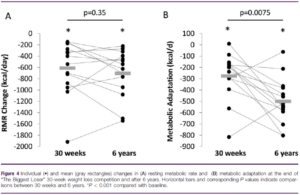

At the end of the show, their resting metabolisms were ~275 calories less than what would be expected. That phenomenon is known as “metabolic adaptation”. Their resting metabolisms 6 years later was ~500 calories less than expected. That’s even after they put weight back on!

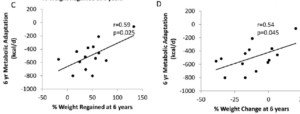

Interestingly, this persistent metabolic adaptation was not correlated with their metabolisms at the end of the show. The degree of persistent metabolic adaptation was correlated with the 6 years later weight. Those who had regained the least amount of weight after 6 years had more metabolic adaptation. Those who gained more weight over 6 years had less metabolic adaptation.

How about their bloodwork? Triglycerides, HDL, adiponectin, T4, and leptin were the only things that did not return to their starting (when the show began vs ended) levels.

- Triglyceride levels increased from when the contestants were at their lowest weights, though not as high as their starting levels.

- HDL remained as high as when they finished the show.

- Adiponectin levels went up higher than when they finished the show.

- T4 levels stayed below what they ended the show with.

- Leptin levels increased by half as much as they dropped during the show.

All other results of the blood work were no different between the start of the show and 6 years later. None of the changes in their bloodwork correlated with their weight or metabolism stats. The researchers clarified that there was not enough power in this group to detect statistical associations with the blood tests. A larger group would be needed to properly test those associations.

Thoughts & Implications

While this group is small in number and they lost weight in a very public way, their results still provides us with information about how physiology can be affected in the long run by great amounts of weight loss over a “short” time.

This group lost an average of 128 lbs in ~4 months. That’s an average of over 4 lbs lost each week. As we know from the show, sometimes they lost more each week and sometimes they lost less. Regardless, that’s a lot of weight to lose in 4 months. That’s far more than anyone usually loses in 4 months. We should not overgeneralize these results. They speak to the possible physiology of dramatic weight loss only. In the paper, the researchers even explained that studies on metabolic adaptation in more “normal” weight loss scenarios are mixed on whether there is any adaptation. When there is, it’s on the order of 3-5%.

Are there any other studies that looked at a different group who lost a lot of weight? Well, Hall & Co. actually published a study in 2014 that looked at metabolic adaptation in patients who got gastric bypass surgery. Hall & Co. compared the weight loss and metabolisms of the patients to these “Biggest Loser” contestants. The patients took a year to lose the most weight that they did, and still did not lose as much as the contestants. The patients’ resting metabolisms lowered by ~300 calories a day after 6 months, but returned to their starting levels by 12 months. We see that in another – but not as dramatic as the “Biggest Loser” contestants – weight loss instance, metabolic adaptation was not an issue.

I said in the Results section that those who gained the least amount of weight over the years tended to have more metabolic adaptation. That said, figures 5c & 5d from the paper show how even those who gained weight and had “less” adaptation still had metabolic adaptation to the tune of 200-600 calories. No one in this group fared much better than anyone else!

The last thing that I will note here is that the struggle for these “Biggest Loser” participants is real. Anyone who has lost a large amount of weight knows that personally. These results put numbers to that experience. While their total metabolisms 6 years later are not far off from their starting levels, their resting metabolisms have not recovered. Whether because of metabolic adaptation, old habits, or hormonal changes, maintaining weight loss is not an easy road (highlighted here). Deficit levels for them may be maintenance levels for someone like me, but that doesn’t change the experience of deprivation. These contestants were given an opportunity to change their health and wellness for the better with the possibility of big money. Who among us would not like either of those things? Who among us would not accept the help of trainers and doctors? Neither the researchers who did the study nor the contestants who lost and then gained weight deserve the vitriol I have seen in the comments online.

Plain & Simply

For most people who lose weight, the magnitude and timeline of their weight loss does not compare to these “Biggest Loser” contestants. It is documented that people who have lost more than 10% of their body weight, on average, have slower metabolisms than expected. But as the researchers pointed out, that is on the order of 3-5% lower. The metabolic adaptation that most of us should expect is not enough to break our efforts to maintain the weight we have lost. There are plenty of other factors that will work against us more than a 3-5% metabolic difference will.

Stay tuned…

The media attention to this study has generated a lot of discussion on the internet. We’ll continue this journal club next time in a Q&A fashion. I’ll pull some common thoughts and questions from around the web and we’ll discuss them.

If you have any questions about this study or anything I said, please feel free to leave a comment. I will get back to you and others may have insight to offer, too. If you have any questions or topic suggestions that you would like answered as a post, then please email me at robert@analyticfitness.com.

Don’t forget to like Analytic Fitness on Facebook, or follow me on Twitter or the other social medias!

No Responses